The development of radical political movements and trade unionism was particularly strong amongst mining communities. Whilst these features were weak in Cornwall there are still examples of protest and resistance. Cornwall’s isolation from established structures including the Church attracted Wesley to promote Methodism. Radical opinions were focused within the development of the new religion rather than in civil society. Cornish Methodism was a powerful force in the county and fertile ground for Liberal politics but less so for trade unionism or socialism.

The development of radical political movements and trade unionism was particularly strong amongst mining communities. Whilst these features were weak in Cornwall there are still examples of protest and resistance. Cornwall’s isolation from established structures including the Church attracted Wesley to promote Methodism. Radical opinions were focused within the development of the new religion rather than in civil society. Cornish Methodism was a powerful force in the county and fertile ground for Liberal politics but less so for trade unionism or socialism.

Although the author of the People’s Charter, William Lovett, was born in Cornwall, the Chartist campaign struggled in the county. Richard Spurr, (1800-1855) a cabinet maker from Truro, took up the cause and was arrested by police with drawn cutlasses on 16 January 1840 at the Trades’ Hall, Bethnal Green whilst addressing a meeting of about 700 people. He emigrated to Australia in 1849 where he joined the growing campaign for democracy.

In 1839 Duncan and Lowery, Chartist missionaries in the region reported: “We find that to do good we will have to go over each place twice for the people have never heard of agitation and know nothing of political principles; it is all uphill work”. (reported in The Chartist Movement 1918). A Chartist meeting in Penzance caused panic amongst the authorities. Mr J Skews represented Cornwall at the Chartist Convention of 1845 and reported that “if the county were properly agitated it would be the best Chartist District in the country.” (Northern Star, April 1845)

The system of wage payments that treated workers as self-employed may have weakened collective activity and encouraged individualism. Yet the nature of food riots would seem to imply no lack of solidarity when required. There were many other examples of co-operation. Communities would pool their resources and skills to build chapels in almost every village.

In 1865 unemployed Cornish miners were recruited as strike-breakers in a bitter dispute in Cramlington in Northumberland. On 5th December 1865, a special train brought the Cornish miners to the pit village where they were put up in the empty houses of the evicted strikers. About 150 men accepted an offer from the union of 10 shillings each for them to return home. But more arrived to break the strike. There was some solidarity with the northern workers. In 1867 some 400 Cornish miners met in the Temperance Hall in Liskeard and voted to stop at home until the dispute was settled. Although not welcome by the locals many stayed because there was no work in Cornwall. It took many years for them to be accepted.

More Cornish families moved north in search of work. Hundreds were settled close to the mine at Roose in Cumbria. In the 1881 Census 70 per cent of the population had birth-places in Cornwall and became known as a ‘Cornish village in Furness’. Before the arrival of the Cornish miners Roose was pronounced with a hard ‘s’, as in goose; now it is pronounced ‘Rooze’, due to the Cornish accent.

There were some strikes in Cornwall: 1831 at the Lanescot Mine and over an attempt to form a union at the Consolidated Mines near Redruth in 1842. The development of early agricultural unions also struggled in the county. In 1873 the National Union of Agricultural Workers had some 86,000 members in 982 branches but none in Cornwall.

There were some strikes in Cornwall: 1831 at the Lanescot Mine and over an attempt to form a union at the Consolidated Mines near Redruth in 1842. The development of early agricultural unions also struggled in the county. In 1873 the National Union of Agricultural Workers had some 86,000 members in 982 branches but none in Cornwall.

Miners led a surprise victory in 1885 when Charles Augustus Vansittart Conybeare (1853-1919) was elected as a radical Liberal MP for Camborne. He lost his seat in 1895. Cornwall was restored to its more moderate Liberal politics.

In 1894, Charles Robert Vincent set up a branch of the Marxist Social Democratic Federation. He was a bookseller in Truro but was persuaded to become an organiser for the new Workers Union. In the early 1900s, Beatrice and Sidney Webb claimed that there were only 600 trade unionists out of a workforce of some 125,000. In 1906 Jack Jones, a docker, was the first socialist candidate in Cornwall. He won just 1.5 per cent of the vote in the mining constituency of Camborne being overwhelmed by the Liberal landslide. Jack Jones was an organiser for the Gasworkers and General Labourers Union but it was the Workers Union that led the 1913 Clay Strike.The strike boosted the Cornish Labour Movement.

Cornish Bal Maidens

Bottalack Mine

Women and children worked down or around mines from the earliest times. In Cornwall, they were called Bal Maidens, from a Cornish word for mining place.

The growth of industry boosted demand for Cornish copper. By the 1690s fleets of ships were taking the metal to Gloucestershire and onwards to the new factories of the Midlands. Women were used to ‘dress’ and ‘pick’ the copper. This was a process of washing the ore and picking out the good stones. It was casual and low-paid work. They would also do the cleaning, cooking and laundry at the pit head.

At the Delabole slate quarry women carried slate up to the storage yards and looked after the donkeys. A few worked as ‘slitters’, the most skilled job.

In 1736 Rev William Borlase complained at the difficulty of obtaining female servants because they could get better paid jobs in the mines.

In 1800 some 2,000 women were employed in Cornish mines and over 6,000 by 1851, a third of the workforce. Half of all women in Illogan and Gwennap worked in the mines. By the early 1900s women had all but disappeared from the mining workforce. Some women returned to the mines during the First World War.

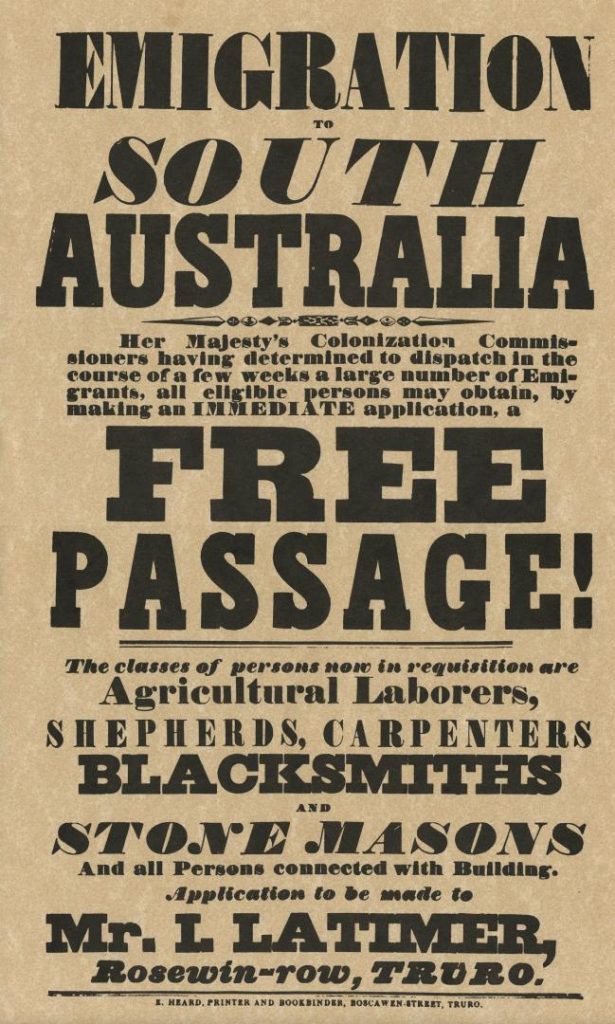

Cornish emigration

Between 1814 and 1914 around a quarter of a million people sought a better life by emigrating from Cornwall. The potato famine hit Cornwall in the 1840s and the crash of copper and tin prices forced families to leave. The crisis amongst Cornish mining communities halted the fragile development of trade unionism just at the time of its growth in areas such as South Wales.

Between 1814 and 1914 around a quarter of a million people sought a better life by emigrating from Cornwall. The potato famine hit Cornwall in the 1840s and the crash of copper and tin prices forced families to leave. The crisis amongst Cornish mining communities halted the fragile development of trade unionism just at the time of its growth in areas such as South Wales.

The development of mining around the world that created a demand for the particular ‘hard rock’ skills of Cornish tin miners. The irony is that many emigrés were amongst the leaders of trade union actions in the mines of Australia. Cornish miners were involved in the Eureka Stockade in 1854 where many died fighting for voting rights.

A statue stands at Bendigo, Australia, in honour of the Cornish miners, with an inscription thanking those miners “who created the economy from which grew a beautiful city”.

A series of strikes in South Australia’s Moonta and Wallaroo copper mines proved successful for the Cornish migrant workforce and a Miners’ Association was established. This was to establish the United Labour Party of South Australia and in 1891 its first MP was Richard Hooper a Cornish Methodist trade unionist. As was John Verra from Gwennap in Cornwall who became the Australian state’s first Labour premier in 1910.

In Cobre, Cuba in the 1840s and the Morro Velho Mine in Brazil in the 1870s, Cornish miners were involved in strikes.

Tom Mathews and James Farquharson Trembarth were Cornish migrants who became pioneers of the labour movement in Johannesburg and Kimberley in South Africa.

The massive emigration from Cornwall meant many families became reliant on wages earned overseas. In 1898 the West Briton reported on the rush on the banks after the arrival of mail from South Africa where many Cornish miners were working. By 1910 some 7,000 miners were in South Africa sending back up to a million pounds a year to Cornwall.

Following the Boer War, the British Government sought to restore South Africa’s mining industry by recruiting up to 60,000 Chinese workers. This policy caused considerable disquiet in Cornwall as some opposed the prospect of the Chinese taking ‘Cornish’ jobs.

The Cornish Diaspora spread around the world. Latin America, Canada, Australia, South Africa and America all have strong Cornish links. At one time it was estimated that in Grass Valley, California, over sixty per cent of the people were Cornish.

The Cornish Diaspora spread around the world. Latin America, Canada, Australia, South Africa and America all have strong Cornish links. At one time it was estimated that in Grass Valley, California, over sixty per cent of the people were Cornish.

The silver mining town of Pachuca in Mexico is known as Mexico’s Little Cornwall. Cornish miners brought football with them, and the town has many examples of Cornish architecture and is famous for its pasties, after the Cornish pasty.

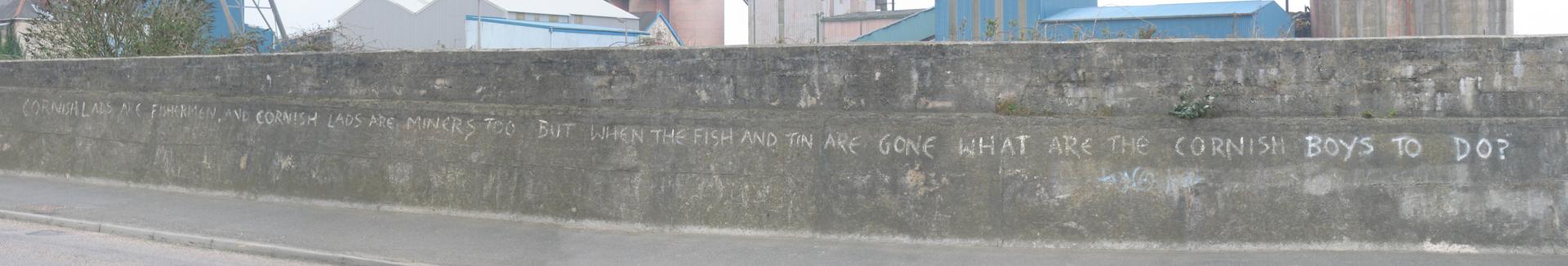

South Crofty, the last working tin mine in Cornwall, struggled to remain commercially viable. There was a big campaign in the county to save the pit. The Thatcher Government pumped in cash to keep it going but it closed in 1998. There are still hopes that mining will return to Cornwall and teh unique geology still holds rare depositis of hard metals and lithium that modern techology needs.

A message on the wall of South Crofty in 1998 taking the words from Roger Bryant’s song in which he asked: “When the fish and tin are gone what are the Cornish boys to do?”