The cloth industry was a central part of the West Country economy in the 18th century. This highly labour-intensive process involved a variety of skills in homes and small mills. But incomes were meagre and livelihoods were threatened with the arrival of new machines. At a time when unions were illegal cloth workers still organised themselves to protect their livelihoods.

In 1717 a widespread combination of cloth workers in Devon and Somerset organised a dispute that led to disturbances in Exeter and Taunton. To show their loyalty they carried royal effigies while they attacked the houses of clothiers! There were attacks against cheap imported Irish cloth in 1720 in Tiverton and at Crediton in 1725, when several hundred workers protested. When the town clerk tried to read the Riot Act, the weavers pulled off his hat and wig and put dirt on his head.

In November 1726 rioting in Wiltshire and Somerset accompanied a strike and in the 1730s there were riots in Tiverton and loom chains cut in Melksham. In 1729, Stephen Feacham, a Kingswood clothier, cut the wages. Angry weavers marched to Feacham’s house where he fired on them killing five people, including the sergeant of the guard with a wayward shot. Although he was found guilty of murder this was over turned by the government. Two weavers who organised the march were hanged for their part in the riot.

In 1738 a Melksham clothier, Henry Coulthurst, had his house and mills wrecked by weavers during a dispute over wages. Some of the rioters were tried and three were executed. There were further riots in 1747 and 1750 and dragoons were sent to the town to help keep order.

New machines

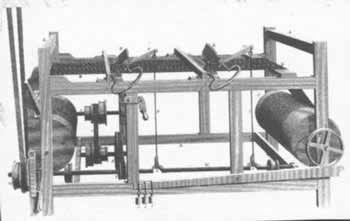

The Spinning Jenny was invented by James Hargreaves in 1764. It could spin eight threads at once and there were claims that new machines could do the job of twenty workers. Violent resistance was felt to be the only option for the cloth workers. In 1767 some 500 shearmen gathered on Corsley Heath to march on a mill in Horningsham, near Warminster and Frome, to pull down a new gig machine.

The Spinning Jenny was invented by James Hargreaves in 1764. It could spin eight threads at once and there were claims that new machines could do the job of twenty workers. Violent resistance was felt to be the only option for the cloth workers. In 1767 some 500 shearmen gathered on Corsley Heath to march on a mill in Horningsham, near Warminster and Frome, to pull down a new gig machine.

James May, a leading Wiltshire shearman, led an underground union in Warminster and Trowbridge. In 1769 the Master Clothier of Melksham complained that journeymen had established an “unlawful and arbitrary combination”.

In July 1776, a group of clothiers in Shepton Mallet introduced Spinning Jennies. Wool workers from neighbouring towns marched to protest at the ‘trial’ that threatened to devastate family incomes. They broke into the workhouse and destroyed the Jennies. A magistrate ordered the arrest of the ring-leaders and five or six were captured. The crowd counter-attacked and the Riot Act was read. The troops fired on the crowd killing one person and wounding six.

In June 1781 Spinning Jennies were installed in a mill in Frome. On Whit Monday the crowd smashed the machines. In March 1790, Keynsham cloth workers joined with local miners to protest against their introduction. The resistance took a tragic turn outside Westbury House in Bradford-on-Avon in May 1791 when some 500 cloth workers gathered to stop Joseph Phelps, a prominent clothier, from introducing scribbling machines. Phelps fired on the crowd killing a man and mortally wounding two others. The coroner found a verdict of ‘justifiable homicide’ and Phelps was awarded £250 damages!

Troops were stationed in the main Wiltshire woollen towns to put down the rebellions but in August 1792 they were called away to break a strike amongst Mendip miners. Cloth workers seized their chance and smashed the machines and despite the troop intervention, the colliers won their pay rise. More riots were sparked in Shepton Mallet and Westbury in 1794 over new scribbling engines. In December 1797, 200-300 Somerset shearers, with blackened faces and armed with bludgeons attacked mills near Frome.

Gloucestershire clothiers managed to introduce the new machines but not without some resistance. Paul and Nathaniel Wathen, a cloth firm in Woodchester, near Stroud, pioneered the use of the shearing frame. On the night of 13th January 1800 there was an attack on their stock of cloths. The employers in the area offered a large reward and Joseph Stephens was arrested. The verdict was guilty and he was hanged. Before his execution Joseph expressed contrition and warned others not to attempt any revenge for his harsh punishment.

The turn of the century saw a down-turn in trade and fearful of competition from Gloucestershire, the Wiltshire clothiers stepped up mechanisation. In 1802 Warminster shearmen went on strike against gig mills. There was an attack on a cloth cart at Calstone Mills, near Devizes and Clifford Mill at Beckingham was burned down.

‘Wiltshire Outrages’

Shearing was a highly skilled craft and better paid than most jobs in the wool trade. Since Tudor times, the work of the shearmen had been protected by law but advancing mechanisation and powerful mill owners had weakened their rights. With inadequate poor relief the shearmen organised themselves in unions. Although unions were outlawed, the shearmen of Trowbridge had a closed-shop and their union cards declared: “Industry, Freedom and Friendship.” In the summer of 1802 the Trowbridge shearmen went on strike.

During the stoppage, Littleton Mill, near the town, was burned down with the cost put at £8,000. This incident led the mill owners to back off from the threatened pay cuts. The employers, however, were determined to break the power of the workers. James Read, a Bow Street magistrate, was sent to Wiltshire by the Secretary of State. He wanted evidence against the union and he arrested Thomas Bailey, a Trowbridge shearman. In gaol and under interrogation, Bailey cracked and told of the union committee and secret oaths.

James May, Secretary, George Marks, John Helliker, (elder brother of Thomas) Samuel Ferris and Philip Edwards were arrested and charged with administering an illegal oath. They were held for seven months. The men claimed that they had been in the New Cross Keys pub, discussing the system of ‘truck’ payments – where employers pay in goods instead of wages. Thomas Bailey had accepted ‘truck’ but promised on a bible not to do so again. The explanation led to their release but Thomas Helliker was not so lucky.

Thomas Helliker

Helliker Day is marked each year with wreaths laid on his tomb in Trowbridge. This was the scene in 2010

Thomas Helliker was in the middle of his apprenticeship when new machines arrived in Trowbridge that led to the strike. The wealthy magistrate and mill-owner, John Jones demanded revenge for the arson attack on the night of 22 July on his Littleton Mill, Semington. Thomas Helliker was arrested on suspicion of threatening a night-watchman with a pistol during the attack. The evidence against Helliker was contradictory and a witness to Helliker’s alleged presence at the scene was given a financial incentive to testify against him by the person who rented the Mill.

A key alibi for Helliker, a fellow apprentice Joseph Warren, went to a magistrate to say that he had found Helliker very drunk on the night of the fire outside a friend’s cottage. He had put Helliker in the kitchen of the friend’s cottage overnight. The front door had been locked and the key had been placed under the cottage owner’s bedroom door. Helliker had slept here until 5am and therefore could not have been involved in the attack. Unfortunately the witness disappeared.

Although protesting his innocence, Helliker refused to betray a fellow member of the shearmen’s union. Helliker was found guilty and hanged on his 19th birthday in 1803 at Fisherton Jail, Salisbury. The shearmen carried his body over Salisbury Plain to be buried in honour in St James Church, Trowbridge. Girls in white dresses led thousands of mourners.

The violence subsided but the resolve of the shearmen was not broken. John Jones continued to face the wrath of local people. In 1808 he was attacked as he rode home from Staverton. A gun shot just missed him and four years later three shearmen were arrested for the attack. There was not enough evidence to make a case for attempted murder. John Jones went bankrupt in 1812.

Life for cloth workers in the West Country continued to deteriorate. Further cases of illegal combination were brought before the courts at Bradford-on-Avon and employers reported that riots in Frome and Warminster in 1822 and 1823 were inspired by a union.

A Parliamentary report conculded that by outlawing unions the legislation made disputes worse and more violent. The Combination Acts were repealed in 1824.

Trowbridge Museum

Trowbridge Museum has a Spinning Jenny on display, one of only five left worldwide and has a display about Thomas Helliker. See more here: www.trowbridgemuseum.co.uk.